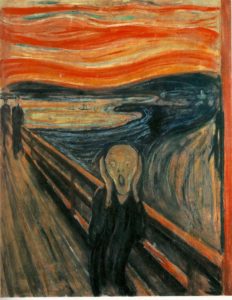

This intense psalm describes a state of frightening loneliness, of abandonment, of God’s face hiding, and of the psalmist’s sense of being a worm rather than human.

This intense psalm describes a state of frightening loneliness, of abandonment, of God’s face hiding, and of the psalmist’s sense of being a worm rather than human.

The metaphor of a worm is striking and unique, precisely because it is so rarely used: it appears only twice, in this psalm and in Isaiah’s prophecy (44).

The Psalm begins with a piercing cry, “Eli, Eli, My God, My God, why have You abandoned me”; a scream of existential loneliness of the psalmist, “You are my God, no one but You has ever been my God, why have You deserted me now?!.” The cry is about a double separation: the spatial distance from God – “until You will not be close to me to be my salvation in times of need,” and the emotional remoteness – “until You cannot even hear my roaring,” and despite my loud cry that can be heard afar, “You would know nothing of my troubles”—abandonment as well as hiding God’s face (Malbim). All these become a daily unbearable pain, “ in the morning I call and you do not respond, and at night I have no respite.”

The depth of despair and loneliness is underscored by the psalmist as he draws a comparison with the secure and intimate relationship of his ancestors, “Our forefathers put their trust in You, they trusted and You rescued them, they trusted and were not disappointed“. And, in contrast to our forefathers, “And I am a worm, a not-human, scorned by men, despised by people.” The historic contrast intensifies the desperate cry from his inner essence that has undergone a metamorphosis. He was a man who has turned no-man, he who was created in God’s image has turned a worm, the lowest of creatures, the scourge of people.

The feeling of being a worm is of about his sense of inner nothingness, of dissolution and of human helplessness. For the psalmist at that point human beings are mere dust, “You commit me to the dust of death”. The worm, crawling in dust, indicates the enormous distance between God who reigns in heaven and the psalmist who is crawling, endangered and beseeching—“Don’t be far from me, for trouble is near and there is none to help.”

In the gratitude verses the psalmist reiterate the worm metaphor, however, he is granted redemption – and at that moment there is none of the distance, “He did not hide His from him” as his cry has been heard.

Psalm 22 begins with unbearable loneliness, abandonment and God’s hiding face, and the psalmist’s sense of being a despised worm, a non-human. The turning point of redemption significantly takes place at the moment when the worm turns to be human again. Grateful, the psalmist gains a sense of relief and consolation and reveals the transformation. The-not -human has become the “I” that God hears and responds by replacing the distance with nearness, “For He did not scorn. He did not spurn the plea of the lowly; He did not hide His from him when he cried out to-He heard.’

****

Translated from the Hebrew by Ayala Emmett