She holds the baby inhaling his sweet smell and kisses his forehead for the last time. She carefully puts him in a wicker basket that she tested over and over, to make sure that it has no leaks and is lightweight enough to float carrying her precious child. She gets as close as she dares to the river, her lips moving in prayer and the tears she tries to hold back are defiant.

She holds the baby inhaling his sweet smell and kisses his forehead for the last time. She carefully puts him in a wicker basket that she tested over and over, to make sure that it has no leaks and is lightweight enough to float carrying her precious child. She gets as close as she dares to the river, her lips moving in prayer and the tears she tries to hold back are defiant.

As we are witnessing it, we are horrified. “Is she mad?” “Should I call 911?” Ready to pull out our cell-phones. Not yet. Right now we are only figuratively witnessing this mother and child. We are together in the text of the Exodus, and the narrator goes on to tell us that the woman we are watching has her daughter at her side. The girl does not cry, “Mother stop.” She does not retrieve the wicker basket; instead, gathering her long dress in one hand she runs following the floating basket down the river, when she hears the laughter of women.

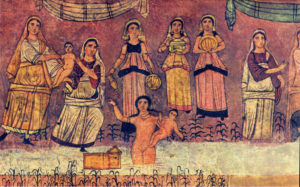

It is a beautiful early sunny morning and the bathing women are splashing each other, shouting names and greetings. One of the women suddenly calls out, “Look,” pointing at the floating little basket. In the unexpected silence, the woman of the highest rank tells one of the maids to fetch the basket, quickly before it floats away. The skilled narrator, who decides what to reveal and what to conceal, chooses to identify her as King Pharaoh’s daughter. She opens the basket and “She saw that it was a child, a boy crying.” [Exodus, Chapter 2, Verse 5].

Now what? Will the princess find a note to identify the baby? The women strain to see and whisper, and we, with our cell-phones and Zooms, can image the murmur, “A mother with postpartum depression?” “An unwed mother?” Or they may be saying something similar in the Egyptian vernacular of the time, which the narrator chooses to let us guess. Pharaoh’s daughter, it seems, does not need an explanatory note, medical, legal, or otherwise. The Exodus narrator records that “She had compassion for him. And she said, ‘He is one of the Hebrew children.’” The crying baby in her arms is a child of the Other, of the despised people, of the slave caste. Swiftly, out of nowhere, on the bank of the river his sister speaks to Pharaoh’s daughter, “Shall I go and get a Hebrew nurse to suckle the child for you?” Such audacity. She could have been arrested on the spot. Or killed. The bathing women watch in silence. The princess answers with calm authority, “Yes.” The girl returns with the child’s mother. The narrator leaves it to us to imagine the emotional energy that now flows between the two women, over and through and beyond their ethnicity, religion and social rank. Pharaoh’s daughter does not waste time, “Take this child and nurse him for me, and I will pay your wages.” In a blink of eye, a bond of trust is forged to save a life. “And the woman took the child. And she nursed him. And when the child grew she brought him to Pharaoh’s daughter, who made him her son, and she named him Moses.”

Years later when Moses, by then an asylum-seeker in the land Midian, sees the Burning Bush he remembers the women who saved his life and recognizes right away that the miraculous is his call to defy despots.

So it is that we enter the earliest biblical liberation narrative, and it begins with women. First come the brave midwives, Shifrah and Puah who defy the despotic Pharaoh, the first in the bible to engage in civil disobedience, when they refused to kill Hebrew baby boys. That is how Yocheved could birth a baby boy who was not killed, but he is in constant danger. What does a desperate mother do?

There have been so many desperate mothers Yocheved, doing everything to save their children. The mothers during the rise of the Nazi regime between 1935-40, who put their precious children on trains to take them to safety, the kindertransport, trusting strangers to have compassion for their children. The desperate mothers in Central America who are sending their endangered children on the unknown journey trusting that we in America would be like Batyah, daughter of Pharaoh, and use our privilege to have compassion for their asylum-seeking children. Like the mothers and the sisters Miriam who stand with BLM, asking our country to finally protect the endangered lives of our children of color. We are the four Exodus women when we stand up and speak up to protect Jews, Asians, LGBTQ and all who are not safe in the USA.

We witness in the ancient text of saving Moses the anguish of desperate mothers in Central America, and the pain of the new/old Jim Craw laws that Republicans are inflicting on us-we are in the 2021 version of the Exodus text. Now is the time to use our cell phones. Let us call our local, state, and Federal elected officials. Tell them we are the descendants of Puah and Shifrah, Yocheved, Miriam, and Pharaoh’s daughter who the sages gave a liberator’s name, Batyah, daughter of God. Let us share with them that in every generation, in every historic moment it is incumbent on us to remember not only that once we were slaves, but we that in every generation women stand up to despots.

May we all have a liberating Passover and put an orange on our Seder plate, to remember the First Women’s Seder and the four biblical women who started liberation.