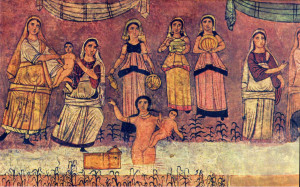

Synagogue Fresco

from 244 CE

This year we add to our Seder Harriet Tubman who joins the six women who shaped the history of the Exodus. The women belong at the Passover table because all seven emerge as consequential political catalysts. All are remarkably brave, amitzot, all are women who at great risk take bold actions in the political/religious arena of their time and speak directly to contemporary concerns of justice.

Tubman joins six agentive women in the Exodus story who are connected across ethnic and class differences.

Who are the biblical women and how do they influence the history of the Exodus? Two of the six are midwives, two are mother and daughter, and two are women of high rank, the daughter of Pharaoh, and the daughter of a Midianite Priest.

The women inscribe courage as a dominant element in the Exodus story that begins in oppression, slavery and attempted genocide. Pharaoh orders the two midwives Shifrah and Puah to do the unthinkable, “when you deliver the Hebrew women look at the birthstool: if it is boy kill him” (1:16). Pharaoh invades the gendered domestic sphere of childbirth and the midwives without hesitation step into the dangerous political terrain. They are defiant, “the midwives who revere* God did not do as the king of Egypt told them.” The two midwives offer us the first biblical lesson in civil disobedience.

The text is (deliberately?) unclear about the identity of Shifrah and Puah. Their ethnicity has been debated in rabbinic commentary; the majority of the rabbis, including Rashi the 12th century commentator identify the midwives as Hebrew women, while other sages view them as Egyptian. Their actions, however, are unambiguous, they defy Pharaoh’s edict to kill all Hebrew newborn boys. Commentators who believe that the midwives are Egyptians praise them for standing up for an oppressed minority. The midwives defiance, regardless of their ethnicity has become a symbol for standing up for the powerless and has been understood as reverence for God.

The midwives defiance makes possible the upcoming events, which focus on the actions of the mother and daughter. The narrative states unequivocally that mother and daughter, whose names at first we don’t know, are Hebrew women of the tribe of Levi, “a certain man from the house of Levi went and married a woman a Levite woman. The woman conceived and bore a son” (2:2). Her son was not killed because the midwives refused to comply with Pharaoh’s edict, which in turn enabled the Hebrew Levite mother to have a live baby boy.

Yet, after three months the mother realizes that she can no longer hide her son. She makes the most heartbreaking decision, to send away her baby in the hope that he would be rescued. The Levite mother constructs a waterproof basket and places her son among the reeds on the Nile. The baby’s sister is watching from a distance as he becomes the first biblical child asylum seeker.

Entering the scene is the fifth woman who immediately knows that this child is of the oppressed minority, “This must be a Hebrew child” (2:7) says Pharaoh’s daughter who without missing a beat decides to take the child. A women’s conspiracy follows, the baby’s sister offers to find a Hebrew woman who would nurse him, the princess agrees, and the boy, still nameless is returned to her weaned, becomes her son and she names him Moses. With few words, mother, sister and adoptive mother (Egyptian) are bonded in saving Moses’ life in defiance of Pharaoh’s violent decree. Moses, as the text tells us, grows up in Pharaoh’s house, kills an oppressive Egyptian task-master, escapes to Midian and marries Zipporah, (a Midianite of high rank), the sixth woman in the Exodus text.

God tells Moses to go back to Egypt to “free my people.” A very reluctant Moses goes back to Egypt with Zipporah his wife and his sons and on the way God wants to kill him.

The “him” that God seeks to kill is not named. The text is far from clear whether God wants to kill Moses or one of his sons, but whoever it is, Zipporah in that critical moment of facing God, acts quickly, she circumcises her son and for unexplained reason it works “and He lets him go.” (4:25).

Zipporah closes the circle of the six women as she, like the others, saves a life by crossing into the religious sphere that could be dangerous if entered inappropriately.

What is appropriate for women in the religious domain has been reinterpreted for generations and in our time we witness greater inclusion in ritual practices. While Miriam has been restored and given a place at the Seder symbolized by placing her cup next to Elijah’s it is time to follow rabbinic Midrashic tradition of honoring by naming, since it is the sages who named Pharaoh’s daughter Batya. We honor at our Seder tonight all six women, the midwives Shifrah and Puah, the mother and daughter Yochebed and Miriam, the princess Batyah and Moses’ wife Ziporah. They all are seminal leaders in the history of the Exodus and this year they are joined by Harriet Tubman.

Harriet Tubman is a woman “who went on to run spy missions for the Union army in the South, including a gunboat expedition that freed more than 700 South Carolina slaves. Harriet Tubman will be the first African-American and the first woman to have her image cast on the front of a currency note.”

Let us follow these biblical women and Harriet Tubman’s unflinching courage. Let us be agents in our time in the political arena to support and stand with all who struggle for freedom here in America, in the Middle East, and around the world.

—

* The Hebrew “vatirena et HaElohim” (1:17) is an idiomatic expression that is best translated as revering God.

This is the fourth in the series Four Women’s Collected Essays on the Meaning of Passover. Click here for introduction to the series. It is republished in 2016.