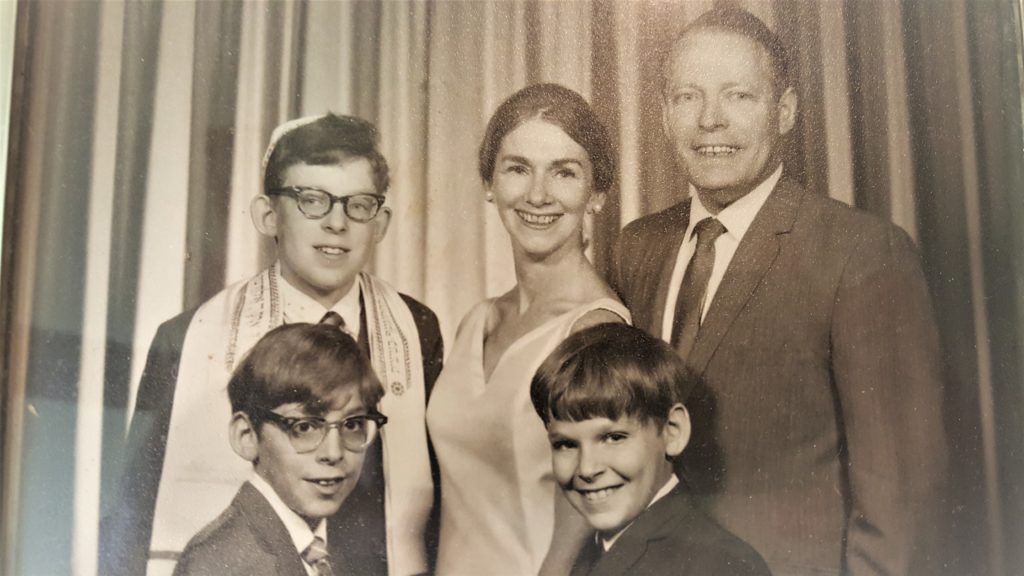

I became a Bar Mitzvah on June 3rd, 1967. This was the last day Israel would ever spend under the boundaries of the 1949 armistice agreements. The Six Day War began the next day, the day you had to begin to distinguish “Israel” from “Pre-1967 Israel.” For half a century I have pondered the possible connection between those two events. Not that I think that my Bar Mitzvah in a small Reform synagogue in Queens had any impact on the course of events half a world away, but I have long thought that through this coincidence and synchronicity somehow the world was trying to send me a message, one that I have yet to figure out.

I became a Bar Mitzvah on June 3rd, 1967. This was the last day Israel would ever spend under the boundaries of the 1949 armistice agreements. The Six Day War began the next day, the day you had to begin to distinguish “Israel” from “Pre-1967 Israel.” For half a century I have pondered the possible connection between those two events. Not that I think that my Bar Mitzvah in a small Reform synagogue in Queens had any impact on the course of events half a world away, but I have long thought that through this coincidence and synchronicity somehow the world was trying to send me a message, one that I have yet to figure out.

Frankly, I don’t remember much about the day, and I don’t remember my thoughts, and those of my friends and family gathered to wish me well, on the course of the perilous events that had brought Israel to the brink of war; the blockade of the Gulf of Aqaba, U Thant pulling the UN peacekeepers from the Sinai, Nasser’s saber rattling, and Israel’s mobilization. What I do remember are the little cocktail knishes served in the hall where we had our reception, and me asking the band to remember asking the band to play, for some stupid reason, that all-time Jewish classic, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” with its multiple references to Christ, though I suppose it was a good day for battle hymns.

My one clear memory is having to chant my haftarah, and then read it in English, from Hosea, in which the prophet likens Israel to a fallen woman, and how embarrassed I was having to talk about stripping women naked and putting things between their breasts before all of my uncles, cousins, and aunts:

Rebuke your mother, rebuke her—

For she is not my wife

And I am not her husband

And let her put away her harlotry from between her face

And her adultery from between her breasts

Else I will strip her naked

And leave her as on the day she was born:

And I will make her like a wilderness,

Render her like desert land.

I forget what I said in my d’var torah. It wasn’t very impressive in any event. If I can have a do-over, using only material I knew by June 1967, perhaps I would cite as my text, taken from a favorite Bob Dylan song “but even the president of the United States sometimes must have to stand naked.” Nakedness is seen in Hosea as a punishment, a humiliation, but of course nakedness can be a spiritual discipline, stripping oneself of covering, of pretense, of anything artificial, and exposing oneself to the elements. On that fateful day, Israel was standing naked in the desert, radically uncertain of its future.

The Six Day War was not a Bar Mitzvah (though Israel was still a country in its adolescence) but like a Bar Mitzvah, it was definitely a rite of passage; joyous, sad, the mark of a profound transition. Looking back to 1967, it’s hard to reclaim or remember my 13-year old self. In many ways I am still the same person; with the same body, more or less, though almost every cell in my body has been replaced multiple times since then. My wife says I still look the same, a beard and a wizening of the features notwithstanding. I am still the same bookish, would-be intellectual I was when I was 13, with a similar range of interests (current events, history, Judaism), but then I am also a totally different person; sadder, wiser, just different. Likewise, Israel is in some ways the country that was created in 1948. In other ways, Israel after 1967 was transformed into a very different country.

I can only thank God that I able to look back at my Bar Mitzvah, half a century ago, with fondness, with a knowledge of the adventures my 13-year old self would undergo, and with the knowledge that, half a century later, the kid is alright. I wish I could say the same about Israel. On June 10, 1967, a week after my Bar Mitzvah, the Six Day War ended, and the occupation began. I look at the history of efforts to end the occupation with sadness, with humility, with a sense of responsibility. Efforts to change and ameliorate the situation began almost as soon as did the occupation. There have been top down efforts, on the highest governmental levels; there have been grass roots initiatives; there have been radicals, liberals, middle of the roaders, and even the occasional conservative involved in peace efforts. There have been successes (Sadat/Begin, withdrawal from the Sinai, peace with Jordan, Oslo) but they are outnumbered by failures. I am humbled because I know that people savvier and cleverer than I, better negotiators, more committed to the struggle, have dedicated their lives to this situation, only to see things get worse. And from the beginning, there has been, and continues to be, violence on every side.

If you haven’t checked it out, I strongly recommend looking at Aliza Rubin’s remarkable on-line American Jewish Peace Archives, a work in progress, that provides capsule biographies and interviews with many persons, from a variety of perspectives, who have, since 1967, tried to fight for Israeli Palestinian peace. (Note: I have in a very small way, tried to assist Aliza in her project.) The range of persons and approaches is astounding. It is one of the rules of political life that when no solution to a problem is obvious or imminent, alternatives proliferate, and so it has been for Israeli Palestinian peace. Aliza’s wonderful archives needs to be supplemented with a Palestinian Peace Archives that would document parallel Palestinian efforts at ending the occupation, which have been even more diverse, and more fissiparous, than those by Israel and American Jews. Wisdom requires humility; I do not know the road that will lead to Israeli Palestinian peace; we need to walk down every road.

Or almost every road. Beware of charlatans and liars. Beware of con men, who, as Gershom Gorenberg has written of our current president, who will play on the desperate hopes and fears of those wanting peace while offering nothing. Let us be broadminded in our search for peace, but let us not be gullible. We have waited half a century for peace; we can wait until the real thing comes along.

In the end, minus all of the sexist language, Hosea was correct. Israel is fallen. My haftarah, which was of course the haftarah for the week of the Six Day War, was indeed prophetic. That week, I was very worried about Israel’s survival. But Hosea makes a distinction between physical and spiritual survival. Israel has survived, and in many ways has prospered. Israel, as a moral force, has not. There are many sides and nations that need to come together to end the occupation, but the major responsibility and initiative will have be Israel’s. The language is old fashioned and totally unrealistic, but I think is honest. Before there can be peace, Israel has to repent; repent of all the injustices it has committed over the past half century, acknowledge that it was and is wrong to deny a people a right to their national existence, wrong to place themselves and their needs over a subject people. If Israel does this, then reconciliation can occur, and the other side can acknowledge their own failings as well.

I was never a very good student of Hebrew, and I don’t think I ever made it to the end of my haftarah. If it starts with God’s condemnation of Israel, it ends with reconciliation, after repentance. We speak of peace, but perhaps we need to restore biblical language and speak of something stronger, more specific and less amorphous and ambiguous than mere “peace.” What the Israelis and Palestinians need is a covenant, something more binding than a treaty, a solemn obligation not to harm one another. To quote the end of the parsha:

I will make a covenant for them with the beasts of the field

the birds of the air

and the creeping things on the ground.

I will also banish bow, sword, and war from the land.

Thus I will let them lie down in safety

I don’t expect to make it to the 100th anniversary of my Bar Mitzvah. But I certainly hope that by 2067, Israel and Palestine would have shared this final rite of passage. And as Hosea reminds us, we have to keep the world a livable place for the beasts, the birds, and the creeping things as well.