Jonathan Siegel suggested that a few of us write about the meaning of Zionism in the wake of the recent Israeli elections. There are few things I like talking about less than “what Zionism means to me.” But since you asked…

Jonathan Siegel suggested that a few of us write about the meaning of Zionism in the wake of the recent Israeli elections. There are few things I like talking about less than “what Zionism means to me.” But since you asked…

Zionism is an example of what the great British socialist and cultural historian Raymond Williams called a “keyword, ” a word that is either blessed or cursed with a multiplicity of shifting definitions, words that often find themselves on the historical barricades, passionately defended and equally passionately attacked. As Williams put it, keywords have “a history and complexity of meanings; conscious changes, or consciously different uses; of innovation, obsolescence, specialization, extension, overlap, transfer.” Zionism is a keyword and trying to give it a neat definition is a fool’s errand. It is a zombie term, a term that has outlived its usefulness, but refuses to die. And “progressive Zionism” is even more obscure, its two parts becoming more oxymoronic every day. In response to Jonathan Siegel’s excellent post, I would only say that if Rabbi Eric Yoffie is a progressive Zionist, then the term has been emptied of all meaning. Reading the same Haaretz articles as Siegel, Yoffie comes across as a tepid, timid Zionist centrist, clinging to a third way that no longer exists, a plague on both your houses politics, Netanyahu bad, left-wing Zionism bad; BDS unmentionable and beyond the pale. It is the sort of politics that was decisively rejected in the recent election, a nostalgic “make Israel great again” politics for a pre-1977 and pre-Begin Israel.

So yes or not, am I a Zionist? I suppose I have to answer yes. However, here is my “but.” My Zionism is a Zionism premised on equality, anti-racism, and an opposition to all forms of Jewish chauvinism. The first “Zionist” activity I remember engaging in was as a newly Bar Mitzvahed 13 year- old, having just joined the left-Zionist organization Hashomer Hatzair, demonstrating in front of the Israeli consulate to the United Nations in late 1967, protesting against the annexation of Jerusalem and what would come to be called “the occupation.” My Zionism is rooted in my love of, and identification with, the Jewish people, not the belief in the Jewish state. I believe that the Jews were entitled to national self-expression, and I am glad that a Jewish state was created, especially as a haven for Jews fleeing persecution. I do not think that the existence of Israel has any religious significance or has fulfilled any prophecies. But I recognize that half of the Jewish people now live in Israel, and what happens in Israel, for better or worse, affects Jews everywhere.

But Zionism was always a special case of nationalism. All national movement have to deal with the minority problem, those people living in their prospective homeland who do not share the dominant ethnicity. Early Zionists had to confront the reality that their prospective homeland, Palestine, was overwhelmingly non-Jewish. This was not the fault of the Jews. There really was no other place for a Jewish homeland, for a host of political and cultural reasons. But it led to an unavoidable and probably unsolvable confrontation with Palestine’s residents. As for the complex history of Jewish and Palestinian relations, who did what to whom first, the rest is commentary.

Zionism has changed the destiny of the Jewish people in at least two fundamental ways. The diaspora, the basic structure of Jewish life for two millennia, is now a duopoly, with about half of the Jewish people living in Israel and 40% of the Jewish people living in the United States. (There were of course other factors in this, but in particular the end of the diasporic nature of Jews in the Middle East was directly tied to the creation of Israel.) And it has created a world in which the Jewish people and the Palestinian people are forever more linked and joined at the hip. All people living under the sovereign control of Israel, in Israel “proper,” in the West Bank, in Gaza, have to be citizens in their own country. A two state solution, in which Palestinians gain a state of their own, is probably the best solution, though freighted with myriad difficulties. As this increasingly seems to be an impossibility, the only alternative is some form of a single state, or a condominium, or any of a number of possible configurations. But the demands of basic equality of all people living in Israel takes precedence over any specifically Jewish structures of the state.

My basic creed is the same it has been for many decades; if there is one lesson I have learned from Jewish history, from studying African American history, it is that no people can be kept permanently submerged and disinherited from what is rightfully theirs. I do not think the current situation is stable, whatever the preponderance of Israeli military might, however long it takes to right this wrong. I do not think that any people can permanently be kept at bay by an occupying army. Zionism has permanently linked the fates of the Jewish and Palestinian peoples, just as African slavery in the Americas has permanently linked the fates of white Europeans and their captives. Zionism has yet to realize that the Jewish state will be a better and stronger state when it recognizes that it has also created a non-Jewish state. About half of those living under Israeli control are Palestinians. They are part of the Zionist future.

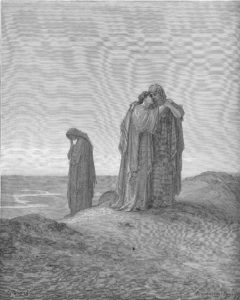

Is this Zionism? Call it what you will. Zionism does not require a Jewish state. It instead looks to the creation of a Jewish homeland where Jews will not be a minority, and will not have to assimilate to be accepted. It will be a vital center for Jewish life. This is the Zionist vision of some early Zionists such as Ahad Ha-Am, who imagined that the Jewish presence in Palestine would be part of a predominantly Arab Middle East. Zionism has not only created a Jewish state, it has created a Jewish and Palestinian state, and both Jews and Palestinians need to recognize this. Perhaps, in the wake of the disastrous election results, left-Zionist parties like Meretz are realizing that there is no alternative to working closely with Palestinians, and the distinction between Zionist and non-Zionist parties is an outdated shibboleth. Realizing this vision will not be easy, but nothing in the history of Zionism has been. Zionism has proven, in its 120 years, to be remarkably adaptive to new circumstances. The challenges and obstacles to this vision are obvious and immense. But it comes down to a commitment to not abandoning either the Jews or the Palestinians who live in sovereign Israel. Democratic inclusion is more important than ethnic particularity. I call this Ruth and Naomi Zionism. I am not going anywhere. This is my home. This is your home. And your people are my people.