Susya: Why We Must Stop Annexation

by Ayala Emmett

with photos by Gili Getz

The protests that flooded the US after the murder of George Floyd by the police have spread anguished cries for justice in this country and around the world. In the following account I describe my visit to Susya, a Palestinian village that is a cry for justice similar to what we have recently witnessed. The local demand for human rights in Susya or Minnesota is universal. Following the protests in America, it is easier to see that the village of Susya reveals ominous implications for Netanyahu’s Trump-supported plot of annexation.

On Monday, January 16, 2017 I was on a bus heading to Susya, in the Southern Hebron Hills in area C. It was a beautiful sunny morning, on the second week of the Israel Symposium, a Partners for Progressive Israel annual trip. Harold Shapiro who had founded the symposium wanted to offer a meaningful experience for those committed to a just Israel. He designed a firsthand tour of meetings with Israelis and Palestinians, a witnessing of life on the ground.

Our bus waited in line at a checkpoint. We were on a tour organized by Breaking the Silence and Nadav Weiman a soldier who served in the West Bank was our guide. He was now committed to speaking up on the impact of occupation on Palestinians. As we waited at the checkpoint a soldier entered our bus asking for passports. I handed her my Israeli identity card and she looked at me, “How long have you been with these people?” Holding my card, she waited and I told her, “I have always been with them.” As her face tightened in displeasure I thought of my own army experience; when I served, my cohorts and I could not have imagined checkpoints or occupation. Yet, after 1967 we like much of the country, splintered, some in my army Nahal unit became settlers, others joined peace organizations, a few refused to serve miluim, reserve duty in the territories.

The young soldier on the bus threw my identity card at me. It landed on my lap and I felt my heart pounding. Every fiber in me wanted to respond with outrage; but I was not about to jeopardize the Symposium trip. I just put my card back in my purse. Someone on the bus asked to go to the bathroom; she refused and told our driver, “Go!“

We have all been through passport inspection, entering and leaving state borders. But this was not a border between states. We have now entered Area C, which represents 60 per cent of the occupied West Bank and is under Israeli administration; its status was designed in 1993 in the Oslo Accord as an interim short phase that had now become a de facto military administration. There are about 200,000 Palestinians living in area C.

Someone asked our guide about the different areas dividing the West Bank. Nadav clarified that under the Oslo Accord, area A has been under Palestinian Authority in both civil and security matters, and area B has been under Palestinian civic administration and Israeli security, and area C was to be a temporary phase under total Israeli civil and security administration.

Much of what we heard from Nadav had been published by Israeli and international media, and NGO publications. Since Oslo, and over the years, what was designed as temporary became an ad hoc harsh and arbitrary military administration that created a hierarchical separation between Israelis and Palestinians. This structure is similar to the racism that fueled the socio-structural separation of black and white America and its consequence, including police brutality, was largely ignored. The Israeli administration in area C has maintained a segregation that was meant to conceal daily human rights abuses. A visit to places like Susya however reveals the power of inequity that is literally visible to the eye. Palestinians have to go through different checkpoints, drive on different inferior unpaved roads; they are not allowed to build at all, and have no local civil authority to which they could turn for services, or seek justice. Over the years all of their appeals to Israel High Court have been denied.

Susya is among eight Palestinian villages in the South Hebron Hills that Israel refuses to recognize their right to their land. Like Susya these villages have been under a perpetual order of expulsions. Israel has taken over water sources in Area C and has restricted Palestinian access to it.

On our way to Susya we stopped on a hill overlooking a valley of fertile fields taken over by settlers. Nadav took out a map and pointed out what used to be Palestinian farmland and had been taken over by illegal settlements; although for all intents and purposes all settlements receive the same military protection and infrastructure services. Suddenly, three settlers came over, insisting that they wanted to talk to us. They had guns. It was a tense moment and we decided to leave. A group of soldiers stood not far away, just watching; the settlers finally desisted and we left. We drove to Susya on unpaved bumpy roads and we arrived at a village in tatters, dotted with cave dwellings and patched up tents.

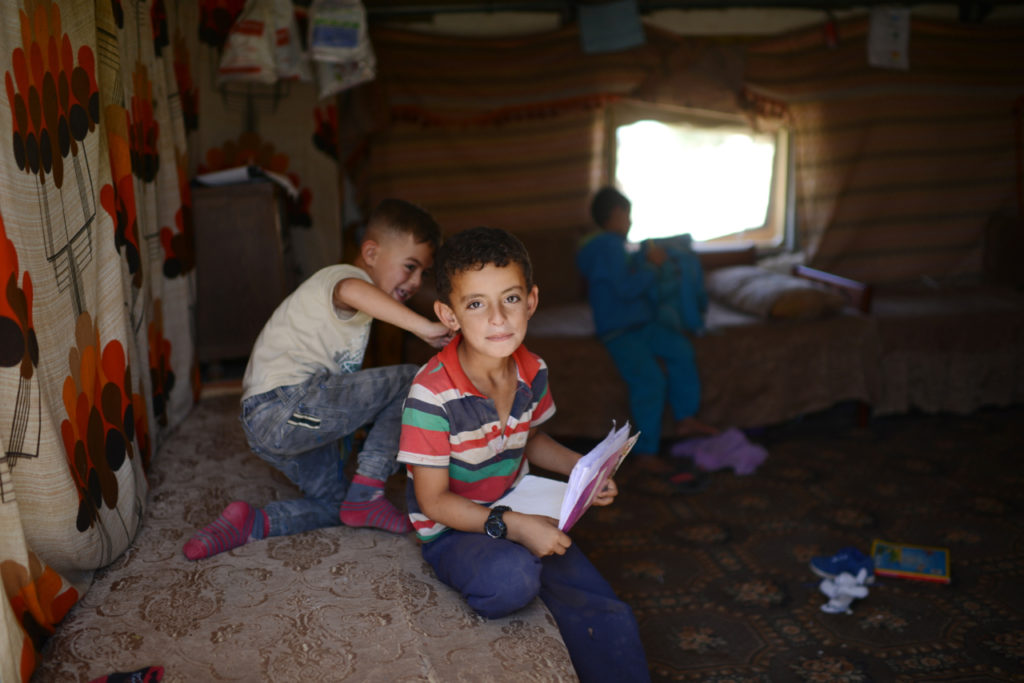

We were hosted by one of the cave dwelling families, chairs were brought out and coffee was offered, children ran around. Our host, one of Susya’s leaders talked about the village history of five evacuations that started in 1986. With every expulsion, the people of Susya returned, determined to rebuild their lives.

As he was speaking I was reminded of a long Jewish experience of expulsions including the city of Frankfurt that my father and later his family left when Hitler came to power. My father came to Palestine and the family followed. Throughout Frankfurt’s history for six centuries, Jews experienced periods of a thriving life disrupted by periodic killings, massacres, forced conversions and repeated returns to build anew.

The people of Susya tried to build again and again, yet faced repeated demolitions. The official Israeli reason given for the Susya perpetual evacuations was that the government declared the site a national park, claiming historic archeological remains of an ancient synagogue.

In 2017 the people of Susya lived in caves and tents. They decided that buildings would be demolished so caves and tents would be home. It was impossible for me to forget our Jewish history of expulsions and denial of rights, for centuries, in Europe and the Iberian Peninsula. It was hard to face that what we saw in Susya had been our doing. Remembering history meant watching the children of Susya who were born into a life of evacuations, constant threats, the absence of any of the most basic services; it all made suffering and violation of human rights so tangible, visible, and painful.

Susya was in such stark contrast to what we saw the day before when we visited a settlement with all the amenities of an affluent town. For me, going to a settlement was an anguished experience; years ago when my relatives moved to a settlement I told them I would never go and would be unable to join their family gatherings. I decide to break my neder and for the first time in my life I went to a settlement. Our host invited us to his beautiful house surrounded by a blooming lush garden; he talked about the kind of life the settlement had to offer, a state of the art hospital, first-rate schools, community centers, a swimming pool and a park. Twenty-four hours later we were in Susya that looked as though we landed in a place outside of history.

On that sunny day in January2017, we had no idea that Netanyahu, with Trump’s ill-advised support, would announce his plan to annex area C. Yet, the place was already a de-facto occupation/annexation. Palestinian Susya as the rest of area C had no human rights. With the Israeli government’s overt and covert blessing, the settlers protected by soldiers, confiscated lands, arbitrarily closed roads, burned fields, cut down trees, displayed guns, arrested children and created a regime of terror.

The remoteness of a village like Susya had allowed concealments of daily abuses and the total absence of the most basic services. In my interviews with Israelis in 2017 most of them had not heard of the Palestinian village Susya; they were only familiar with the settlement of Susya, a religious communal settlement of the same name as the village that falls under the jurisdiction of Har Hebron Regional Council. It has become easy for Israeli Jews to not know or ignore the facts on the ground, which prompted groups like Breaking the Silence to speak up about the abuses of the occupation. The soldier who checked my identity card was the face of the anger that the Right in Israel displays at any revelation of Palestinian de facto annexation that until Trump’s presidency had no official American support.

This Netanyahu/Trump plot of annexation has disaster written all over it, particularly at this moment of American protests’ cry for justice. Annexation would cause damage at multiple levels. For Susya and the rest of the area it would mean continued endless, daily suffering and brutal threats. Formal annexation would destroy any shred of Palestinian hope for an end to their plight that we heard in Susya. It is hard to imagine that settlers in the Area C or Netanyahu’s government would ever grant any human rights, or voting rights to the Palestinians. There has been plenty of evidence to the contrary.

Annexation would have socioeconomic consequences for Israelis increasing the enormous economic price that settlements have extracted. Annexation would be at the expense of reducing already meager resources for underserved communities within the 1967 borders. Politically in the region, annexation would threaten Israel’s fragile relations with Jordan and Egypt. The Palestinian Authority has already revoked its agreement with Israel, including security coordination. The Arab league has issued a warning not to implement annexation, as did some European states.

There is a slim, but increased chance now to stop annexation. On Saturday, June 5 there was a protest in Tel Aviv to stop annexation that was inspired by the protests following the murder of George Floyd. The protest of annexation in Israel thus merged with the growing universal cries for justice. Meretz members of Knesset participated in the protest and Chairman Nitzan Horowitz had a clear warning: “Annexation is a war crime. A crime against peace, a crime against democracy, a crime that will cost us in blood.” The Head of the Joint List Ayman Odeh drew an analogy with the American moment of justice, “We are at a crossroads. One path leads to a joint society with a real democracy, civil and national equality for Arab citizens … The second path leads to hatred, violence, annexation and apartheid. We’re here in Rabin Square to pick the first path. There is no such thing as democracy for Jews alone. Just like Martin Luther King and his supporters in the United States, we must realize that without justice there can be no peace. And there will be no social justice if we do not end the occupation.”

The spread of the protests from Minneapolis to Tel Aviv could become a moment to turn the tide of endemic structural racism in the US and to put an end to a cruel 53 years of occupation/ annexation. If we all stand up and speak up we can turn the tide for justice and peace that we heard from Tegan, a 17-year-old Israeli Arab. She came to protest in Tel Aviv from Taibeh and said, “I’m protesting because enough with all this bloodshed. We need to make peace between Jews and Arabs now. Enough racism, enough murder, we’re just over it. Bibi and Trump are racists and I’m a little, a lot, afraid of what will happen if there’s annexation. Last week I was at the women’s march and we want to tell the politicians that enough is enough.”

Susya, the story of Palestinian anguish reflects the universal call for justice in the US and in Israel. Let us stop annexation and put an end to 53 years of occupation. Let us draw on Jewish history to pursue justice, Tzedek, Tzedek.

| Ayala Emmett is Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Rochester. Born in Tel Aviv, she grew up in a religious socialist Zionist community in Israel, and served in the Israeli army. Professor Emmett is the author of Our Sister’s Promised Land: Women, Politics, and Israeli Palestinian Coexistence and of numerous articles on peace, justice, gender, and religion. She is the recipient of the Society for Humanistic Anthropology Fiction Award. Professor Emmett is the founder and co-editor of The Jewish Pluralist, a digital publication that gives space to American and Israeli voices commenting on Jewish and non-Jewish life and committed to Jewish values and ethics.

Gili Getz is an Israeli-American photojournalist, actor, and activist. He served as a photographer for the Israeli military and the news editor of YnetUS. In recent years, his worked has focused on Jewish-American politics and is published regularly in Jewish and Israeli press. His photography is published by Princeton University Press in the book Trouble in the Tribe: The American Jewish Conflict over Israel by Professor Dov Waxman. His one-man play The Forbidden Conversation explores the challenges of having a conversation about Israel in the American Jewish community. He has a new photography book in the works focusing on the Jewish Resistance to Trump and the Occupation. |