It is always a good time to think about, to read, and now to watch Abraham Joshua Heschel. There is even a better reason now. There is a new film, just out from Journey Films, directed and produced by Martin Doblmeier, Spiritual Audacity: The Abraham Joshua Heschel Story.

“What manner of man is the prophet?,” asks Abraham Joshua Heschel, in the opening words of his 1962 masterwork The Prophets. Heschel tells us. The prophet has an acute sensitivity to evil. Acts that others might dismiss with a shrug, or explain away as the dog-eat-dog way of the world, incite the full fury of their indignation at what Heschel calls “the secret obscenity of sheer unfairness.” This the prophet feels fiercely, a sensitivity to evil that is a divine illness. They know that God has placed a burden on their shoulders, and thrust a coal into their mouths. The prophet feels the pathos of God, and becomes its vessel. The prophet is an iconoclast, a breaker of images, a seeker of holiness who has no patience or tolerance for its feigned imitations or facsimiles, an unwelcome guest in the Temple. The prophet decries evil and the pollution of the divine word, but is aware that to castigate only the wicked lets everyone else off the hook, and in Heschel’s famous words, “few are guilty, all are responsible.” All misdemeanors become felonies. But in this refusal to accept gradations of accountability they are insisting on our linked fates, that God is less interested in the fate of individuals than our collectivities, our communities, cities, and nations. Prophets are bringers of both comfort and wrath. And so while prophets are not sentimental, they are compassionate, recognizing human shortcomings and limitations, and that because of this, our shared fate will never eliminate desperation and suffering.

Abraham Joshua Heschel was in the English-speaking world, and in the Jewish world, the most influential writer on the Hebrew prophets of his time. It is probably an occupational hazard of writing about prophets to be considered one. Shortly before Heschel’s death in 1972, in an interview with NBC reporter Carl Stern, he was asked “Well, are you a prophet?” Like all true prophets, he answered in the negative, saying I won’t accept this praise.” What else can a prophet say? If Carl Stern had interviewed Jeremiah or Isaiah, they no doubt would have evaded the question as well. A prophet with too much honor, who is too respected, who is only greeted and treated with reverence is a prophet whose prophetic edge has been dulled and blunted. They can only bring a butter knife to life’s sword fight. A prophet is judged by the enemies they have made.

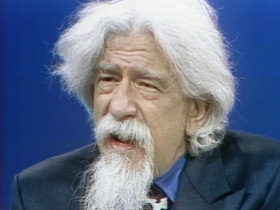

Let us take Abraham Joshua Heschel at his word. He was not a prophet. But he looked like a prophet, fitting in with the hirsute 60’s with his white mane of hair and flowing wispy beard. And he sounded like a prophet, mixing his war against political and spiritual complacency by speaking of God’s search for humanity and the radical amazement of finding this God, preaching a theology of passion and involvement. And like a prophet, wherever he turned his gaze he found God, and places suffering because of God’s absence. He found God in the Black Freedom Struggle, arms locked with Martin Luther King, Jr in the Selma voting rights march of 1965, which became one of the enduring iconic images of the era. He spoke out in defense of beleaguered Russian Jewry in the Soviet Union and against the American atrocity of the War in Vietnam. And he was a pioneer in interfaith outreach, perhaps most notably in his extended efforts during Vatican II to get the Roman Catholic Church to repudiate its two-thousand-year-old anti-Jewish dogmas. He believed that “no religion is an island” to quote the title of one of his most famous articles. So perhaps he wasn’t a prophet, but as he told Carl Stern, “it is arrogant enough to say that I am a descendant of the prophets, what is called a B’nai Nevi’im.” In the end, I don’t think Heschel cared when he was called. All he wanted to be listened to, with the arrogance of someone who knew that he had something important to say, and with the humbling knowledge that at the same time, he was too frail, too imperfect, and too befuddled a messenger for God’s message.

Martin Doblmeier, Spiritual Audacity: The Abraham Joshua Heschel Story includes interview material with Heschel along with commentary from his daughter, Susannah Heschel, a leading scholar of Judaism in her own right, Michael Lerner, Shai Held, Cornell West and many others. The film tells the story of his remarkable life. Heschel was born in Warsaw in 1907. Both parents were descended from prominent Hasidic rebbes. His immersion in Hasidic culture and learning is one of the keys to understanding Heschel. Perhaps my favorite among his books is A Passion for Truth (1973), a study of two Hasidic rebbes, the Ba’al Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism, and Menahem Mendel of Kotzk (1787–1859), (along with having a substantial detour into the angst-filled religion of the Danish Protestant theologian of existential angst, Søren Kierkegaard [1813–1855.]) For Heschel, if the Ba’al Shem Tov preached and practiced a religion of inclusion and of spiritual equality, the Kotzker rebbe and Kierkegaard were practitioners of a religion of nervous intensity and interiority, and despisers of any religion that smacked of self-satisfaction. Kierkegaard and the Kotzker rebbe, who spent the last twenty years of his life in seclusion, raise the question for Heschel of how to handle spiritual truths; whether to restrict them to a small circle of adepts and acolytes, and keep them pristine, or spread them more widely, and risk their adulteration. Like most in the Hasidic tradition, he believed in the latter, while respecting the “passion for truth” that animated difficult, uncompromising religious seekers like the Kotzker rebbe.

Heschel, a Hasidic prodigy, did not follow a traditional Hasidic path, and chose to study in an academic Gymnasium in Vilna, and then went to Berlin in 1927, participating in the remarkable but tragic efflorescence of Jewish studies in Weimar Germany. Heschel shared, with writers such as Martin Buber, Gershom Scholem, and Franz Rosenzweig, a rejection of both the staid rationality of classic Reform Judaism and the Haskalah, and the legalism of Orthodoxy, and instead focused on the importance of direct religious experience and the search to craft a new religious modernity. In Germany he published several books, the first edition of his study of the prophets, and short biographical studies of Maimonides and Isaac Abravanel (1437–1508.) Heschel remained in Germany until 1938, serving the increasingly beleaguered Jewish community there, until he was expelled in 1938, and after a harrowing trip and confinement on the German-Polish border, returned to Warsaw.

However, Heschel, very afraid of the possibility of a German invasion, was eager to get out of Poland. In July 1939, six weeks before the Nazi invasion, he was able to leave for Britain, and then arrived in New York City in March 1940. (His mother and sisters and other family members perished in the Holocaust. He dedicated The Prophets to “the martyrs of 1940–45.”) He spent the war years teaching at Hebrew Union College, which had arranged for him to come to the United States, for which he was forever grateful, but he did not find the religious atmosphere at the Reform seminary particularly congenial, and in 1946 he began teaching at the Jewish Theological Seminary in upper Manhattan, the main seminary for the Conservative movement, where he would teach for the remainder of his career. The theological outlook was closer to his own views, but he remained something of an outsider on the faculty, whose leading members focused on detailed “scientific” textual studies of the Talmud, and who often saw him as something of a lightweight, a dispenser of trite sermonic homilies, a writer of accessible books rather than dense articles in obscure scholarly journals. In their dismissal of Heschel’s weightiness, they could not have been more wrong. Anyone reading his Hebrew language Torah min Hashamayim—translated as Heavenly Torah—could have no doubt about his Talmudic chops, but he rightly felt that he needed to write in a different style to reach American Jews (and Americans in general.)

After he was settled in New York, his books came out in a torrent. He was one of a number of European emigres who arrived just as the war was breaking out who rapidly mastered a richly idiomatic American English, Jewish theology’s answer to Vladimir Nabokov. It was primarily his books in the late 1940s and 1950s that secured his American reputation; The Earth is the Lord’s (1949), his incredibly moving elegy to his lost culture of eastern European Jewish culture, The Sabbath (1951), and what are probably his two most important influential books, Man is Not Alone (1951), and God in Search of Man (1955.) Heschel’s best writing is aphoristic, a theology of insight and acute observation, approaching God not through definition and theological proposition but metaphor. Although written at the height of the vogue of existentialism and much talk about the age of anxiety, Heschel’s books have often impressed me with their lack of hand-wringing about God’s distance from humanity. It is rather a celebration, of God, the Jewish people, and people in general, and the “radical amazement” of belief. Heschel does not make God difficult to find, and if anything, and he has little patience with unbelief. At times he seems to think that since God is so real and present to him, anyone who hasn’t found God just isn’t trying hard enough.

It is a minor paradox of sorts that if you read Heschel’s major works of the 1950s, I don’t think one would have predicted that in the 1960s Heschel would be best known as a social activist. It is not that this dimension of Heschel’s thought is absent in his earlier work, but it was not its focus. Perhaps this is a reflection of the times. The 1950s was a decade in which there was much discussion of a religious revival, in which Will Herberg’s triad, Protestant/Catholic/Jew became America’s official trinity. It is perhaps instructive to compare Heschel to a previous rabbinic celebrity, Joshua Loth Liebman (1901–1948), whose 1946 book, Peace of Mind, spent a year as #1 on the New York Times best seller list. It is a book that can be judged by its title, a call for the finding of a personal and collective postwar calm after the hurly-burly of global combat and catastrophe, its sonorous tones edging into complacency, being at ease in Zion. It is a celebration of the serenity that can come from a deep connection to God, but Heschel offers a prophetic serenity, a confidence in God’s message that leads outward, toward challenging unearned self-satisfaction, a serenity that is closest to God when the messenger is pissing off the right people.

In this, Heschel was hardly alone. He was part of a group of religious thinkers in mid-twentieth century America, who differed in many ways, but shared a general outlook; liberal or radical in their politics, radical in their insistence on the direct experience of God; inspired by the promise of America, outraged by its failures. For Martin Doblmeier, the head of Journey films, and a longtime director of documentary films on religious subjects, this is the fourth film he has made in recent years on mid-century religious figures. The first film was An American Conscience: The Reinhold Niebuhr Story (2017), followed by Backs Against the Wall: The Howard Thurman Story (2019), Revolution of the Heart: The Dorothy Day Story (2020), and now the film on Heschel. (I should note in the interests of full disclosure that I was interviewed for the film on Thurman.) All of the films are available as CDs, and have been broadcast on PBS. The subjects of Doblmeier’s films make for quite a quartet: Two Protestants, one Catholic, one Jew; one African American, one woman; one immigrant; two pacifists; one Cold Warrior.

They were each quite distinct in their lives and their religious thinking, and at the same time, their lives were often entwined, borrowing and sharing insights among them. Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971) was a good friend of both Howard Thurman (1899-1981) and Heschel. Heschel and Thurman were both good friends with Martin Luther King, Jr. Dorothy Day (1898–1980) and Thurman were both pacifists, and worked closely with pacifist organizations and were close to the religious pacifist A.J. Muste (1885–1967), someone else who belongs in this little band of prophets.

The four religious figures of Doblmeier’s films shared a rejection of the liberal theology of the early 20th century, which they felt was often a religion of complacence, both in matters spiritual and political. The oldest among them, Niebuhr, and the only white male Protestant among them, was the first to come to mainstream attention, especially with his blunderbuss of a book, Moral Man and Immoral Society (1932) which criticized the Social Gospel for its focus on individual redemption as the basis of societal transformation, and for purveying a liberal theology that had forgotten real meaning of sin. As Heschel, who came to know Niebuhr when they were teaching in adjacent upper West Side seminaries, wrote after Niebuhr’s passing: “He began his teaching at a time when religious thinking in America was shallow, insipid, impotent, bringing life and power to theology, to the understanding of the human situation.” Thurman, born poor and Black in Florida in 1899, by dint of intelligence, luck, and ambition, became a noted mystic and advocate of radical nonviolence. His 1949 book, Jesus and the Disinherited, is the best book on American democracy that most people who write about American democracy have never read, and he was a major influence on King. Thurman and Niebuhr were friends from the mid-1920s on. In 1932, at a commencement ceremony at Thurman’s alma mater, Morehouse College, the historically Black college in Atlanta, Thurman delivered the benediction while Niebuhr delivered the main address, cautioning the graduates against “aping middle class white life,” urging them to avoid “the rut of bourgeois existence.” He doubted whether “the majority group of white people will ever be unselfish” because “power makes selfishness.” Rather than preaching platitudinous sermons, Black Christians needed to confront white supremacy not with goodness but a religiously-inspired realism about power. Because he thought pacifism was just another high-minded effort by persons of good will to evade political reality, Niebuhr was a sharp critic of pacifism, and Niebuhr’s politics by the late 1930s were interventionist, strongly supporting the war effort. On the other hand, in 1936, his good friend Howard Thurman, his wife, Sue Bailey Thurman, and one other man became the first Black Americans to meet with Mahatma Gandhi, the leader of the Indian independence movement, and famed practitioner of radical nonviolence. Thurman had been a pacifist since the early 1920s. After their meeting, Gandhi gave Thurman and the others a benediction: “It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of non-violence will be delivered to the world.” In the 1920s, Dorothy Day, the one-time Greenwich Village radical, wearying of the bohemian life, and looking for something more stable and substantial, joined the Catholic Church, and within a few years started the Catholic Worker movement, dedicated to the rights of labor, radical insurgency against capitalism, the practice of poverty, the caring for the poor and outcast, as well as the teachings of the church. During the Cold War and War in Vietnam, Day’s outspokenness won her a number of new admirers.

Martin Doblmeier made these films because he felt that the cause of progressive religion has been neglected and largely forgotten by the mainstream media. As someone who has worked extensively on the life and works of Howard Thurman, I have found that the most common response to the statement: “I am writing a biography of Howard Thurman” is, “who?”

In recent decades the focus on religion in the United States has been almost exclusively about the rise and aggressive exercise of political power by the religious right and evangelical Christianity. Progresssive religion is now commonly reduced to an oddity, a contradiction in terms, milquetoast apologists for a religion of inclusion, or just RINOs, religious in name only. They are treated as the losers in the struggle for the soul of America, with the hard, unbending intolerance of the hard right as the smug and contemptuous victors.

This is wrong on so many levels. First, the religious right has to be seen as a reaction against the success of progressive religion and its role in sparking the civil rights movement. As has so often happened in this country, the backlash, the reaction, was stronger than the initial action. And perhaps most importantly, religion is simply too important as a social glue to be abandoned to those who think the only role of religion is to exclude and anathemize, to create an exclusive club with God as the bouncer. Progressive religion, those who seek God’s presence as an inspiration for the personal and public lives, is not finished.

On the other hand, the future of progressive religion is uncertain. All four of the subjects of Doblmeier’s films have had their successors, students, and sedulous biographers, but they did not create self-perpetuating movements. (The exception is Dorothy Day. The Catholic Worker Movement still publishes the Catholic Worker, and it still runs over two hundred “houses of hospitality” in the United States and elsewhere. And she is the subject of an active, ongoing effort for her canonization, and the only one of the four likely to be declared, at some point, a saint.) The institutions of progressive religion continue to exist, but at times they feel like redoubts in a land controlled by their enemies.

One final comment: It is no doubt unfair on my part, but it seems that in recent decades, that the progressive religious left has produced no one with the stature of a Niebuhr, a Heschel, a Thurman, a Day, or a King. Chalk this up to my ignorance, or my lack of distance and appreciation of the spiritual leaders of our own times. Or perhaps the progressive left has become more suspicious of charisma and charismatic leadership than it was sixty years ago. It is striking that in the fights against global warming, or in the Black Lives Matter movement, no single figure has emerged as a dominant leader, and this is not unintended. Perhaps in our polarized times we can no longer cross the divide between the secular and the sacred, with the ease of the subjects of Doblmeier’s films. All I can say is that whether or not we are all just epigones, there is much to learn from the glorious history of progressive religion in twentieth century America, for inspiration, for consolation, and the occasional prophetic kick in the pants.

Anyone needing an introduction, a refresher course on who they were, or to spend some time in conversation with four men and women who spent their lives walking with God, could do much worse that watching the films of Martin Doblmeier. And why not start with his latest release on that rabbi of rabbis, that rebbe of rebbes, Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Peter Eisenstadt is the editor and author of many books, most recently Against the Hounds of Hell: A Biography of Howard Thurman (2021)