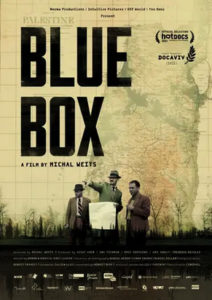

It’s difficult enough for an individual to understand and come to terms with the actions and psychology of their family. It’s even more complex when a revered and beloved relation is part of the country’s history where you were born. Michal Weits, the director of “Blue Box,” is confronted by both challenges.

It’s difficult enough for an individual to understand and come to terms with the actions and psychology of their family. It’s even more complex when a revered and beloved relation is part of the country’s history where you were born. Michal Weits, the director of “Blue Box,” is confronted by both challenges.

It’s not surprising that her documentary took her fourteen years to complete.

Aided by remarkable archival footage and the 5,000 pages of personal diaries of her great-grandfather, Yosef Weitz, she embarks on a trek to deconstruct her forbearer’s beliefs and the actualities that built the state of Israel.

It’s not a pleasant journey.

Weitz is part of a younger group of filmmakers featured at the 2021 New York Other Israel film festival. They are taking on the myths that she and Israelis (not to mention American Jews) have been raised on.

Despite documentation and her great-grandfather’s journals at her fingertips, weaning Israelophiles away from romantic visions of Israel’s establishment is not for the faint-hearted.

Michal lays out how Weitz was integral to the “national narrative of state-building.” The promoted concept of an “empty, neglected land” and the oft-repeated phrase, “A land without a people for a people without a land,” turns out to be a false and empty slogan that has served to make reality more palatable.

Michal lays out how Weitz was integral to the “national narrative of state-building.” The promoted concept of an “empty, neglected land” and the oft-repeated phrase, “A land without a people for a people without a land,” turns out to be a false and empty slogan that has served to make reality more palatable.

“The Father of Israel’s Forests” also had an appellation of a very different sort: “The Architect of Transfer.” As Michal traces the story of her great-grandfather, she confronts the fact that he “didn’t see room for two peoples on the land.” She reveals that in looking at the majesty of Israel’s forests, she only saw “beauty before cracks appeared.”

Michal keeps track of the population demographics of Israel/Palestine throughout the film. The first map, dated 1910, shows 80,000 Jews and 650,000 Arabs.

In 1908, an 18-year-old Weitz left his birthplace of Russia to follow the Zionist dream in the Holy Land. He was appointed the Director of Department of Lands at the Jewish National Fund, known as the “Blue Box fund to buy land,” in 1932. His work included heading the Department of Lands and the Department of Afforestation. The task: To acquire extensive acreage from Arabs and absentee landlords. The latter, living as far away as Damascus and Cairo, collected taxes from the tenant farmers.

In a visit to Ramallah, Weitz noted in his writings that the city showed a “thriving community of Arab homes and agriculture.” The Arab tenants did not understand the reason for their evictions. Weitz assuaged his conscience with the rationalization, “We paid good money for it.”

There were 175,000 Jews and 800,000 Arabs in 1933. Although Weitz continues full speed ahead with land acquisitions, he comments on the “wound” inflicted and is prescient enough to foresee that it “would never heal.”

Arabs in Palestine began to resist the land purchases by 1936. They want independent rule and a stop to the flow of Jewish immigration. In addition to mobilizing strikes, they raise funds to buy tracts of territory—to keep them out of the hands of Jews. Riots ensue. By 1937, the British concluded that the territory needed division. As a response, Jews used the strategy of constructing settlements to expand the borders.

The meticulous writings of Weitz reflect his inner thoughts. In 1940, he determined that there was “no room for both peoples.” Believing a compromise was not viable, his conclusion paved the way for an Israel without Arabs. The concept of a “total transfer” became the only way forward.

After World War II, launching Israel was deemed a proactive response to the Holocaust. European refugees who couldn’t go home needed a place to live. When Weits questioned her family members about the decisions made, the generalized response reflected the idea that “it was a different world…one in which a tiny nation was trying to survive.”

With the declaration and establishment of the Jewish state in 1948, 750,000 Arabs were expelled or fled from their villages. The new numbers on the 1948 map show 650,000 Jews and 156,000 remaining Arabs. In Haifa, out of a population of 50,000 Arabs, only 5,000 remained.

In her map graphic, Michal uses orange dots to represent Arab towns and villages. After the 1948 war, the dots are sucked off the map with the sound of a swoosh and disappear. Watching footage of people trudging down roads with bundles or a single suitcase, it’s impossible not to have the mental image of European Jews forced to abandon their homes and known way of life.

A Custodian of Absentee Property is appointed in the interim to oversee the uninhabited homes and villages that stand empty.

Weitz sees the available properties as a “miracle.” When inspecting the emptied areas, he decided to “preclude any possibility of Arab return.” With a list of abandoned villages in hand, Weitz determined that under no conditions should the Arab inhabitants be permitted to return. His philosophy included financial restitution and a resettlement program in adjacent countries—where the refugees would “be better off.”

To implement the permanent departure of Arabs, a Transfer Committee was established. Using the chilling and historically ironic words, Weitz records, “We drafted a scheme for resolving the Arab question.”

No return, demolition, resettlement, and replacement were the formula. David Ben-Gurion was on board.

In conversations with her family, Michal is told, “What Grandpa really wanted was to take care of his own people.” Her uncles suggest that her conclusions are “exaggerated.” They invoke the wars and other Arab nations that participated and insisted, “No one owed them anything.” It was all about “nation-building.” Denial blanketed the conversations.

Regardless, Michal maintains, “There’s a serious moral problem here.” She shares, “I learned to read the landscape around me…We pass the ruins and choose not to see them.”

The underpinnings for land rights issues began when Ben-Gurion sold 250,000 acres of absentee lands to the Jewish National Fund. In essence, by transferring land to an “extra-national” body, the state of Israel could sidestep the jurisdiction of international law. Weitz questioned if that action was permittable.

JNF is tasked with developing the lands. To underwrite the project, they solicit monetary support from Diaspora Jews.

In 1950, the Israeli Parliament codified the Absentee Property Law, which made confiscation of Arab properties permanent and precluded the return of refugees. Israel was no longer the custodian, and the JNF was free to settle the grounds and plant trees. Weitz began the job of getting 80 million trees in the ground.

Michal’s uncles assert that “every war produces refugees” and that it is “too late to discuss” what transpired. Weitz himself grappled with the displacement of Arabs, seeing financial restitution as a solution.

Successive governments ignored the festering catastrophe. Like Ben-Gurion, they convinced themselves the problem would disappear.

Weitz resigned from JNF leadership in 1965, after thirty-five years of service. The following year, he recorded in his journal that he had been “banished from the public sphere.”

After the 1967 war, Weitz clearly understood that Israel would not be able to repeat the methods used in 1948 in the West Bank and Gaza. Palestinian residents were not going to abandon their homes.

At a post-screening conversation, Michal said, “We did something wrong. We need to acknowledge the past.”

Aided by the chronicles of her great-grandfather, who put his unembellished thoughts down on paper, perhaps together the two of them may be able to set the record straight.

Images: Norma Productions/Blue Box

The article was first published on The Blogs of The Times of Israel

Marcia G. Yerman is a writer based in New York City. She writes profiles, interviews, essays, and articles focusing on women’s issues, human rights, Israel/Palestine, politics, culture and the arts. Her articles are archived at mgyerman.com. Find her on Twitter at @mgyerman.