As the last Holocaust survivors die, despite documentation and recorded oral histories, the connection to lived experience disappears with them.

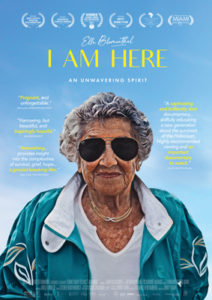

In “I’m Still Here,” the story of Ella Blumenthal is recounted against the backdrop of her 98th birthday. (She is currently 100 years old.) Surrounded by her children, grandchildren, and friends, for the first time she fully reveals the details of her five-year ordeal during World War II. She has previously withheld them from those closest to her.

The cheerful demeanor of an older woman in a green running suit may be the image she presents to the world, but her personal history is always with her–like the twenty-four relatives she lost in the Holocaust.

The story of each person who lived through Nazi horrors has similarities and differences. What they have in common is that moment when a person or circumstance interceded, saving them from death.

Director Jordy Sank interweaves Ella’s monologues of revelation with personal photos, archival material, and animated sequences in earth tones, greys, and black. The latter serves to move the narrative forward, conveying the gruesome aspects without feeling exploitative.

Bella’s story begins with her birth in 1921 into a Warsaw household where she was the youngest of 7 children. Her days included singing, dancing, kayaking, and a happy Jewish home life. Despite warnings from her brother that it was time to leave Poland, there was a belief that nothing could happen to them. That ended in 1939.

A year later, the Nazis pushed the Jews into the Warsaw Ghetto, where they faced malnutrition and starvation. Deportations to Treblinka, from which people didn’t return, accounted for the loss of most of her relations.

After the Warsaw uprising was crushed, buildings were set on fire, making hiding impossible. Bella explains that the sights, sounds, and smells are always in front of her. “I can never erase it from my mind.”

Along with her father and niece Roma, she was shipped to Majdanek in 1943, when she was 21. She and Roma were chosen to live. Her father was not. It was the last time Ella saw him.

Public hangings established the fate of prisoners who tried to escape. A brush with the gas chamber ended only at the last second. Bella describes “German orderliness” as what saved her. There were instructions to exterminate five hundred women, not 700. She was part of the 200 that received a reprieve.

Bella relates, “I never lost hope. Never. Not even in the darkest times of my life.” Her emotional fortitude prevented Roma from killing herself on electrified barbed wire. That strength kept them both going during the final two years of captivity, which began with a transfer to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1943.

After having her head shaved, Bella was tattooed with the number 48632 and a triangle beneath, signifying that she was Jewish. A Christian Polish childhood friend, serving as a nurse in the camp, prolonged her chances of survival.

Outdoor conditions were brutal. Bella tried to get work indoors and was offered the opportunity to be the “head of a block.” Responsibilities included hitting other inmates and turning over the sick and weak girls for the gas chamber.

She refused.

Finding a loose page from a Haggadah gave her renewed resolve. She still has the piece of paper today. “Someone up there is looking after me…I don’t think it was just luck.”

In 1945, she and Roma were transferred to Bergen-Belsen. While working in the kitchen, a Russian prisoner saved her from punishment after she stole potatoes. Her obsession that “no food must be wasted” never ceased.

When Bella witnessed the gradual disappearance of German guards at the towers and the systematic destruction of records and papers by camp personnel, she realized that a shift was coming. In April 1945, American soldiers liberated the camp.

A trip to her home in Poland confirmed that no one had come back. After going to Paris with Roma, Bella voyaged to Palestine by boat. There, she met the South African man who would become her husband, Issac Blumenthal. They married after a thirteen-day whirlwind courtship. “It was like a dream,” Bella recounts.

Her new in-laws in Johannesburg suggested that she have her tattoo surgically removed and forget the past. She didn’t discuss her experiences or the truth behind the scar on her arm, but her sons and daughter innately understood that something about their mother was different. Her screams in the middle of the night confirmed their intuitions. (She finally explained that they were the product of dreams where Nazis took her children.)

Several of the film’s scenes are shot on-site at the Capetown Holocaust & Genocide Centre. The setting creates a connective tissue between the lessons of the Holocaust and injustice in all forms. The museum’s mission is to serve as a platform for dialogue about additional genocides, the history of apartheid in South Africa, and issues of morality in terms of antipathy toward “the other.”

Ella notes, “There is more that unites us than divides us. I want to understand human nature…What difference does survival make if you didn’t learn a lesson about humanity?”

It was hard not to think of parallel conditions when she spoke of Jewish land requisitioned in Poland.

Bella’s experiences are connected to her Jewish heritage; however, it doesn’t prevent her from seeing beyond the tragedy that impacted the Jews. She repeats her top insights in various iterations and expresses them most succinctly in the following thoughts:

“The hatred is not only for Jews. The hatred. That’s what’s causing all the problems in the world. So we must love people around us. Not find fault with the color of skin or different beliefs. Love everybody. Be kind to everybody.”

Marcia G. Yerman is a writer based in New York City. She writes profiles, interviews, essays, and articles focusing on women’s issues, human rights, Israel/Palestine, politics, culture and the arts. Her articles are archived at mgyerman.com. Find her on Twitter at @mgyerman.

This article was first posted in The Times of Israel