Let me add a few thoughts on Ayala’s wonderful d’var Torah on parshat Tzav. The priests were the first Jewish professionals; the first responders to the sinfulness of the Israelites. Their position was hereditary, but they needed to be trained in their specific tasks; they needed to don specific garments to be used only while performing their assigned roles.

Let me add a few thoughts on Ayala’s wonderful d’var Torah on parshat Tzav. The priests were the first Jewish professionals; the first responders to the sinfulness of the Israelites. Their position was hereditary, but they needed to be trained in their specific tasks; they needed to don specific garments to be used only while performing their assigned roles.

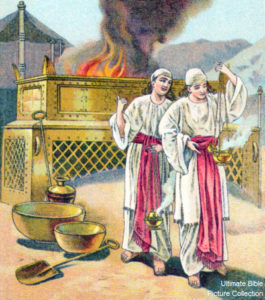

What is a professional? Persons who have special education for a specific role they perform for the rest of society. They need to be licensed in some fashion, and they are generally respected for their abilities. Many professionals have dangerous jobs. That was certainly true for Israelite priests. They were the intermediaries between humanity and God. In this week’s parsha, in Sh’mini we have the story of Nadab and Abihu—the priests who offered God “strange fire” and were in turn incinerated by God. The interpretations of the sad fate of Nadab and Abihu are many. But perhaps what is most important is that the priests who wrote Leviticus thought this story was so important that they interrupted their recitation of laws to highlight the lesson that professionals always need, whatever the situation, whatever their crisis, to remember both their strengths and limitations.

Professionals need to take themselves seriously, and demand the respect owing to their standing as professionals. Sometimes professionals have to fight for this. Traditionally female professions, such as nurses, have long fought to be recognized as more than mere subordinates. Professionals from minority groups have often had to confront the condescension of those who believed, for instance, that a black man or woman could not be a good doctor, dentist, or lawyer.

But there is also the opposite problem; of professionals taking themselves too seriously, thinking that their status grants them privileges they haven’t earned, that they have nothing in common with the people they serve, or even more dangerously, that somehow their training enabled them to be exempt from their own rules; physicians who think they cannot get sick; lawyers who think themselves above the law; or priests who think they cannot sin. Professionals have to follow the routines of their profession without getting trapped within them. They cannot become jaded. When you’re performing your 6th bull sacrifice of the day, it’s easy to forget that for the person bringing the bull, it’s probably his first bull. (I have long wondered if priests were just butchers, or whether they also provided counsel, comfort, or advice to those coming to them to discharge their ritual obligations.)

The way to avoid getting trapped in a professional routine, is for the professional to remember they are part of a bigger community, and it is not rules and regulations of their profession, but service to others, that makes them professionals. The Torah portion makes the essential point; the priests were part of the Israelite community, and not above it, serving God but not God-like, not above the transgressions that were the fate of all Israelites. And this is a time to appreciate all the professionals who are keeping our society running at the time of this dire crisis; our nurses, our doctors, our health care professionals, and other professionals who usually get less respect; the housekeeping staff of hospitals; home health care aides; the people who drive the trucks and the trains, the clerks who put things on the shelves of our supermarkets. Despite the gross and grotesque incompetence of some of our leaders, it will be the professionals, performing their essential duties, that will keep our society intact, and let us honor their dedication. And I think the priests that wrote Leviticus, who knew dedicated professionals when they saw them, would have agreed.