The Women In Exodus:Two thoughts on Parshat Sh’mot

I. Six Women in Exodus—Ayala Emmett

Six women emerge as consequential political catalysts in the opening chapters of Exodus. All of them are women who make daring bold choices that move them beyond domestic/gender roles placing them in the dangerous political/religious arena. All display astonishing courage in the face of powerful threats and all underscore the value of the sanctity of life. Of the six, two are midwives, two are mother and daughter, and two are women of high rank, the daughter of Pharaoh, and the daughter of the Midianite Priest.

The number of women is significant since much of Torah is about men and the opening chapter of the book of Exodus begins with the naming of all sons of Jacob; yet Torah narrative occasionally pays attention to women, among them Eve, Sarah, Hagar, Rebecca, Leah, Rachel, Bilhah, Zilpah and Dinah. Nowhere else, however, does Torah give voice in one single Parsha to six agentive women who are all connected despite ethnic and class differences.

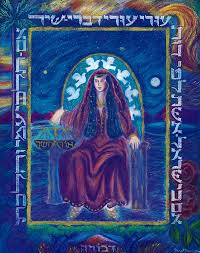

The narrative states unambiguously that two of the women, mother and daughter, whose names we still don’t know, are Hebrew women of the tribe of Levi. We learn that two are non-Hebrew, the daughter of Pharaoh who has a distinguished Egyptian pedigree and Zipporah who is the daughter of a Midianite Priest. About the identity of the two midwives, Shifrah and Puah, the text is unclear; their ethnic identity has been debated, the majority of the rabbis, including Rashi the 12th century commentator, identify the midwives as Hebrew women, other sages view them as Egyptian. Their actions, however, are unambiguous, they defy Pharaoh’s edict to kill all Hebrew newborn boys. Commentators who believe that the midwives are Egyptians praise them for standing up for an oppressed minority. The midwives defiance, regardless of their ethnic identity has become a symbol for standing up for the powerless and they are described in the narrative as women who revere God, who follow/fear God.

The six women are all connected beginning with the midwives’ act of defiance. The Hebrew Levite woman could save her baby boy because the midwives refused Pharaoh’s decree. Yet, after three months she realizes that she could no longer hide him, and makes the most heartbreaking decision, we can only imagine the strength that a mother needs to give up her baby son in the hope that he would be saved. The Levite mother constructs a waterproof basket and places her son among the reeds on the Nile hoping for the best. The baby’s sister is watching from a distance.

Entering the scene is the fifth woman who immediately knows that this child is of the oppressed minority, “This must be a Hebrew child” (2:7) says Pharaoh’s daughter who without missing a beat decides to take the child. A women’s conspiracy follows, the baby’s sister offers to find a Hebrew woman who would nurse him, the princess agrees, and the boy, still nameless is returned to her weaned, becomes her son and she names him Moses. With few words, mother, sister and adoptive mother (Egyptian) are bonded in saving Moses’ life in defiance of Pharaoh’s violent decree. Moses, as the text tells us, grows up in Pharaoh’s house, kills an oppressive Egyptian task-master, escapes to Midian and marries Zipporah, (a Midianite), the sixth woman in the Torah reading.

God tells Moses to go back to Egypt to “free my people.” A very reluctant Moses goes back to Egypt with Zipporah his wife and his sons and on the way God wants to kill him. The “him” that God seeks to kill is not named. The text is far from clear whether God wants to kill Moses or one of his sons, but whoever it is, Zipporah in that critical moment of facing God, acts quickly, she circumcises her son and for unexplained reason it works “and He lets him go.” (4:25). Zipporah closes the circle of the six women as she, like the others saves a life. While women are not major social actors in Torah, when their presence is acknowledged it is often as exceptional social agents and history shapers. read more