What does a father do when he realizes that he has favored one of his children and created sibling rivalry and hatred among them? When it comes to favoring a child, most parents would claim that they treat all their children equally. Yet children may feel and experience the relationship differently. Some may feel special, while others feel less appreciated and not loved enough. Parents may be unaware of their own actions when they single a child by showering favors, or praises that make other sibling feel envious, slighted and resentful.

What does a father do when he realizes that he has favored one of his children and created sibling rivalry and hatred among them? When it comes to favoring a child, most parents would claim that they treat all their children equally. Yet children may feel and experience the relationship differently. Some may feel special, while others feel less appreciated and not loved enough. Parents may be unaware of their own actions when they single a child by showering favors, or praises that make other sibling feel envious, slighted and resentful.

A father’s special love for a son is the underlying tragic thread in the Joseph story that occupies the last part of the Book of Genesis. Joseph is the first son born to Jacob’s beloved wife Rachel, who dies giving birth to Joseph’s younger brother, Benjamin. In the narrative of love, marriage and loss, Joseph is the son of a happy marital moment. Jacob clearly and openly favors Joseph who feels entitled. Nine of Jacob’ children are sons of three other mothers none of whom is like the beloved Rachel, and that marital differentiation has already planted resentments, and the brothers are united in hating Joseph.

Jacob has been a father who shows favoritism publicly in the coat of many colors he gifts Joseph and is astonishingly blind to the toxic dynamic he has created for his sons. He manages to ignore the feelings of anger as he decides, it seems on whim, to send Joseph to look for his brothers who are far away from home. Joseph participates in the denial. Not a word of protest from the son who could have said, “Should I go father, surely the brothers hate me.” And a doomed reunion ensues. When the brothers see Joseph they first want to kill him. They end up, with some intervention from two older brothers, to sell him into slavery.

The Genesis narrative tells us that upon returning home the brothers tell Jacob that a wild beast has attacked and devoured his son. They have the ultimate revenge proof as they bring back the special coat that Jacob made for Joseph, soaked in blood. In the years that Jacob mourns his son, Joseph has come up in the world, rising from a Hebrew slave to become a political power in Egypt, second only to Pharaoh.

Years later when father and son meet again in Egypt the narrative does not include any conversation between them about the past. The father, however, tells Pharaoh who asks how old he is, that his years have been bad, indicating that he has not measured up to his ancestors. It is an unexpected answer to a question about age, yet it is Jacob’s step in a new humility. He makes a public statement that his life was far from perfect, and would become a steppingstone in his choice to make amends at the end of his life. When Joseph hears that his father is on his deathbed he goes to Goshen to see Jacob, this time as a father himself as he brings his two sons. They may not know it, but they are there for a purpose and not just to get a patriarch’s blessing.

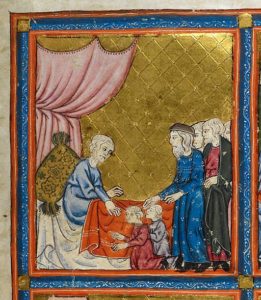

Jacob does something extraordinary. He takes Joseph out of the generation of the sibling group and installs instead his two sons. They take their father’s place as Jacob adds his grandchildren to the house of Israel as two tribes. He makes it clear that there is going to be no tribe of Joseph. Jacob elevates his two grandchildren, Ephraim and Manasseh and in an instant, and with no explanation, places them in the sibling group of future tribes. He anoints the nephews, to be “like brothers” to their uncles.

At this late stage, shortly before his death, Jacob understands the enormity of what he has done and the brothers’ resentment that has been so intense that they were ready to kill Joseph. To leave Joseph as a brother among his brothers would no longer be possible. He was also at that stage of their family history so elevated politically that returning to the domestic sibling group, as a brother/tribe would continue to inflame relations. Replacing Joseph with his sons would ameliorate and diffuse the sibling hatred. Joseph gets a blessing as a son, not a brother/tribe.

On this coming Shabbat as we read Parshat Va-Y’hi, [Genesis 37-50] we already know that the generational shift Jacob has created has worked. There is never a hint in the Torah that Ephraim and Manasseh, Joseph’s sons, were out of order in the sibling group. In replacing Joseph in the sibling group Jacob signals both regret and redemption. Jacob realizes that he could not change the past but he could affect the future.

Many thanks to Matia Kam and Shiloh Kam for their comments.