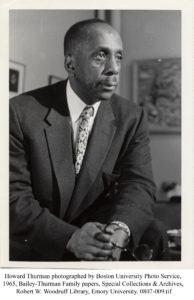

On 3 December, 1963, the African American minister and religious thinker, Howard Thurman (1899–1981) and his wife, Sue Bailey Thurman (1903–1993) arrived in Israel for a stay of several weeks. They had wanted to visit Israel during a previous, round-the-world trip, in 1960, when they visited Lebanon—where he had talks with Palestinian refugees—and Egypt, but the ongoing Arab boycott had made this impossible. They arrived in Israel after an extended stay in Nigeria, where Howard Thurman had been teaching at the University of Ibadan.

On 3 December, 1963, the African American minister and religious thinker, Howard Thurman (1899–1981) and his wife, Sue Bailey Thurman (1903–1993) arrived in Israel for a stay of several weeks. They had wanted to visit Israel during a previous, round-the-world trip, in 1960, when they visited Lebanon—where he had talks with Palestinian refugees—and Egypt, but the ongoing Arab boycott had made this impossible. They arrived in Israel after an extended stay in Nigeria, where Howard Thurman had been teaching at the University of Ibadan.

One of the most important aspects of Thurman’s religious and social thought was a deep philosemitism, an admiration of both Jews and Judaism. His lifelong Jewish friends ranged from Jack Schooler, a Rochester haberdasher who helped the young Thurman, a Floridian who had never seen snow before, studying at Rochester Theological Seminary, equip himself for the rigors of that city’s winters, to Rabbi Joseph Glaser, executive vice president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, who called Thurman his “teacher and spiritual counselor,” adding, “but for him, I would likely not have become a rabbi, nor seen the glories of the Jewish tradition as fully and vividly as this man. ” Thurman’s most famous book, Jesus and the Disinherited (1949), opened by stating the three most important things to know about Jesus was that he was a Jew, he was a poor Jew, and as a poor Palestinian Jew he was not a Roman citizen, so “he lacked the security of citizenship. If a Roman soldier pushed Jesus into a ditch, he could not appeal to Caesar, he would be just another Jew in a ditch.” For Thurman, the situation of Jews in first century CE Palestine, neither enslaved nor free, staggered and obsessed by their oppressors, had much in common with the condition of Blacks in mid-20th century America.

Thurman also found much to admire in Judaism as a religion. Although he was a Christian minister, his deepest religious commitment was to his personal mystic vision of the unity of life and nature. He often said that he worshipped God, not Jesus, and found the emphasis on the oneness of God at the center of Jewish religious observance immensely moving. He would write that at Jewish worship services, primarily at Reform and Conservative congregations he felt “stripped naked. It seemed to me that there was veil between the worshipper and God.” Throughout his career, he was a frequent guest speaker at numerous Jewish congregations. At the same time, Thurman’s emphasis on the primacy of direct spiritual experience was a challenge to what many found as the overly formal aspects of Jewish worship. He wrote in his autobiography of the “hundreds of hours of talk, of probings of the mind, of sharing the spirit and simple, beautiful connections with many rabbis and their families.” He also considered himself a Zionist, and was outspoken in his support of the admission of Jewish refugees to Mandatory Palestine after World War II. And so, he wrote in his autobiography, “for a long time I had looked forward to a visit to Israel.”

But Howard Thurman did not really like his stay in Israel. He kept a journal during his time in the country. His first entry was “ Israel is an unhappy land,” without explaining why he felt this way. He certainly found most of the Israelis he met to be courteous, going out of their way to be helpful, wanting to show off their country. (Perhaps the relative novelty of African American tourists in Israel in 1963 contributed to this friendliness, but nonetheless, their openness challenges the stereotype of the rude, officious Israeli.) When Howard and Sue went to the central bus station in Tel Aviv asking for directions, a crowd of people clustered around them, offering suggestions. When they purchased a pair of sunglasses in an optician’s shop, and asked for a lunch recommendation, the optician closed her shop and took them to her favorite lunch spot. People offered to serve as tour guides in both Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. The problem with Israel was not that Israelis weren’t friendly.

The problem, or at least one problem, was he was not prepared for the differences between Judaism as practiced in the United States and Judaism as practiced in Israel. The liberal Judaism that had nourished Thurman in America was largely non-existent in Israel. At Hadassah Hospital he met a famous cancer researcher. He described to the Thurmans his dedication to his research and saving lives. For Thurman, he seemed “so obviously a spiritually minded person that I remarked to him about this.” He responded, “I am a materialist. I have no time for the illusions of religion and its cant. I leave that to those who have nothing else to do or to think about.” He notes that he “was to discover that this attitude was prevalent.”

He had even less patience for Israelis who were religious. While teaching at the Boston University School of Theology, he formed a close bond with his student, Zalman Shachter-Shalomi, who came from a Lubavitcher background, and went on to be a founder of the Havurah, or Jewish Renewal, a Neo-Hasidic movement, that emphasized, like Thurman, the importance of personal religious experience. From the influence of Shachter-Shalomi—who always called Thurman his Black Rebbe—he gained a deeper appreciation of Hasidic spirituality. Thurman tried to arrange a meeting with Martin Buber when he was in Israel. This proved impossible. It would have been a highlight of the trip to Israel. And the Hasidim he saw in Israel were not free spirits like Shachter-Shalomi. In Jerusalem “we went through the section of the city where the Orthodox Rabbis held forth. We saw men in their long, black coats—the beards, side burns, and zealot countenances—but it was all grim and foreboding. I wanted to flee away—this seemed like a rearguard holding the rear lines; a vast retreat covering a rout.” Thurman had spent his entire career fighting against rigid religious orthodoxies and inward-looking religious like the ultra-orthodox Jews he saw in Jerusalem. In his autobiography he wrote, “We were not prepared for Jerusalem. There was nothing in evidence to remind me of what through the years I had come to think of through the years as the city of Jerusalem–I do not desire to see it again.”

Thurman was aware that these thoughts were in some way unfair. He was observing Israel “through the eyes of his own religion,” and he was neither the first nor the last Christian to be overwhelmed by Israel’s near-monopoly on Biblical place names and their resonances, and then disappointed that they did not meet his expectations and imagination. His friend, the prominent Reform rabbi Roland Gittelsohn, on reading his autobiography wrote him: “I wonder if you were not looking for an idealized, almost childish kind of Jerusalem, which you remembered from your early lessons in Christianity.” It was a fair criticism, and we need to remember that in 1963 he was limited to visiting West Jerusalem, and the closest he got to the Old City was viewing the barbed wire and checkpoints of no-man’s land.

And yet, Thurman’s unenthusiastic response to Israel reflected more than just Christian fantasy. He had hoped to share in the excitement of the Jews of his acquaintance, the inheritors of the ancient Jewish dream of return, and like them, catch a whiff of “the scent of the homeland of their forefathers.” But he was “puzzled” that the mood he sensed in Israel was a “political and nationalistic fulfillment rather than merely a spiritual returning or homecoming to a land made sacred by divine encounter.” His disappointed comment on viewing Marc Chagall’s stained glass windows in the chapel of Hadassah Hospital—he found his work superficial, mere decoration— can perhaps stand as a comment on his entire time in Israel: “The place is barren as if it had been deserted by the gods. There was nothing here that gave me as a Gentile any awareness of the great spiritual history of Israel.”

Perhaps, if Thurman perceived Israel as an “unhappy land” it was because a country that was struggling to deal with the shattering weight of the recent Jewish past while trying to confront its difficult present and uncertain future. And it was doing so by keeping their sorrows private and inner life unexamined, And in doing so, they had created a country that was more garrisoned, more militantly secular, and more hidebound in its religious orthodoxy than he had expected. Israel had forgotten the Hebrew prophets.

For Thurman the philosemite, the prophets were the first and the greatest monotheists. They were the first religious thinkers to seriously ponder what it meant when God called a people to form their own nation, and to form a holy nation; they were the first thinkers to grapple with the contradictions of a God that was both national and universal. And from the outset, they believed that a nation whose members lived unexamined lives, and whose collective shortcomings were not exposed and called out, were living contrary to the will of God.

Now, it might be said that Israel, in 1963 or in 2021, had or has more important things to do than to get right with the prophets, problems that do not have any direct relationship to religion; Palestinians, the occupation, the drift to authoritarianism, the growing wealth gap, and so on. Thurman would disagree. Nationalism everywhere is parasitic upon religion and religious conviction. It arose as an alternative “social glue” for the cohesion and sense of community that religion provided. But the dream of secular nationalists of replacing religion with nationalism has been a failure. And perhaps nowhere is the paradoxical relation between religion and nationalism more apparent than in the uneasy marriage of Judaism and Zionism. Contrary to the dreams of secular Zionists, religion will not go away by despising it; contrary to the beliefs of the ultra-orthodox, religion cannot thrive simply by trying to embargo secular modernity and making the ultimate religious value the determination to resist change of any kind. And to the dismay of many of his American Jewish friends, like Rabbi Gittelsohn, Thurman believed that Judaism could not survive if it merely replaced the worship of God with the worship of the Jewish state.

Sometime prophets are too late to be of help. Martin Luther King, Jr., a disciple of Thurman, announced on 15 May, 1967, that he had made arrangements with both the Jordanian and Israeli governments to lead a peace mission to those two countries, with plans for him, that fall, to preach one day in the Jordanian-controlled Old City of Jerusalem, and the next day at a holy site on the Galilee. Of course, this pilgrimage never happened, and within a few weeks of King’s announcement, Israel and that part of the world would be irrevocably changed. And of course, it is very unlikely, even if King’s mission happened, it would have altered the course of Israeli and Palestinian history. But after 1967 Israel, more than ever, has needed prophets. And there have been many prophets in Israel since the time of Thurman’s visit, but as in the Bible, the true prophets are usually without honor, or as Isaiah put it, “despised and shunned.” Or perhaps worse, honored and then not listened to.

When Howard Thurman visited Israel in 1963, his overwhelming impression was a country with a spiritual void. And what he wanted was not for Israelis to find “religion,” certainly not to imitate his own mysticism, but to develop enough inner resources, a moral core, that Thurman would call God but others could provide alternative names, that would enable them to deal with their personal and national lives without paralyzing fear, without lies, without hatred, and above all, without violence. After 1967, the Israel Thurman visited in 1963 would be gone forever. But if Thurman would return to Israel today, he would find much has remained the same. Religion remains a weapon and a cudgel to beat others. And the three great religions that lay claim to historic Palestine have not found a way to creatively use their matchless heritage constructively, to bring warring peoples together. And Thurman might add, if religion cannot, by itself, provide a solution to the problem of Israel and Palestine; religion, if not properly harnessed, will be an impediment, obstacle, and impenetrable barrier to a solution.

Peter Eisenstadt is a co-editor of The Jewish Pluralist. This essay is adapted from his recently published book, Against the Hounds of Hell: A Biography of Howard Thurman (University of Virginia, 2021.) For those interested in Thurman’s writings on the Hebrew Prophets, see Howard Thurman on Moral Struggle and the Prophets, ed. by Peter Eisenstadt and Walter Earl Fluker (Orbis, 2020.)